Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Violinkonzert E-moll

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4632845-1370603820-5143.jpeg.jpg)

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy's Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64, is a cornerstone of the violin repertoire and a beloved piece worldwide. Composed between 1838 and 1844, it stands out for its melodic beauty, technical brilliance, and structural innovation. This article provides a detailed overview of the concerto, its history, structure, and significance, intended for those seeking a comprehensive understanding of this musical masterpiece.

Genesis and History

The concerto's genesis was a protracted affair. Mendelssohn initially conceived the idea in 1838, prompted by his close friend, the violinist Ferdinand David, who was then the concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Mendelssohn sought David's technical expertise throughout the composition process, consulting him on the feasibility and idiomatic nature of the violin part. This collaboration was crucial in shaping the concerto's character. Despite this consultation, the composition process was not straightforward, with Mendelssohn frequently revising and refining the work. The initial impetus for the concerto was likely to fill the gap in Mendelssohn's own compositional catalog - despite writing other concertos, he hadn't focused on the violin.

While Mendelssohn began working on the concerto in 1838, it was not until 1844 that it reached its final form. Several factors contributed to this delay, including Mendelssohn's heavy workload as the music director of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, his extensive travels, and his meticulous approach to composition. He wanted to avoid cliché and predictable virtuosic displays, opting instead for melodic integration and a balanced interplay between soloist and orchestra. The finished work was dedicated to Ferdinand David, and he premiered the concerto on March 13, 1845, in Leipzig, with Niels Gade conducting. Mendelssohn himself was unfortunately unavailable to conduct due to illness.

Structure and Musical Analysis

The concerto is structured in three movements, following the traditional fast-slow-fast pattern, but with a crucial innovation: the movements are linked together, played attacca (without a break). This creates a seamless and unified musical experience.

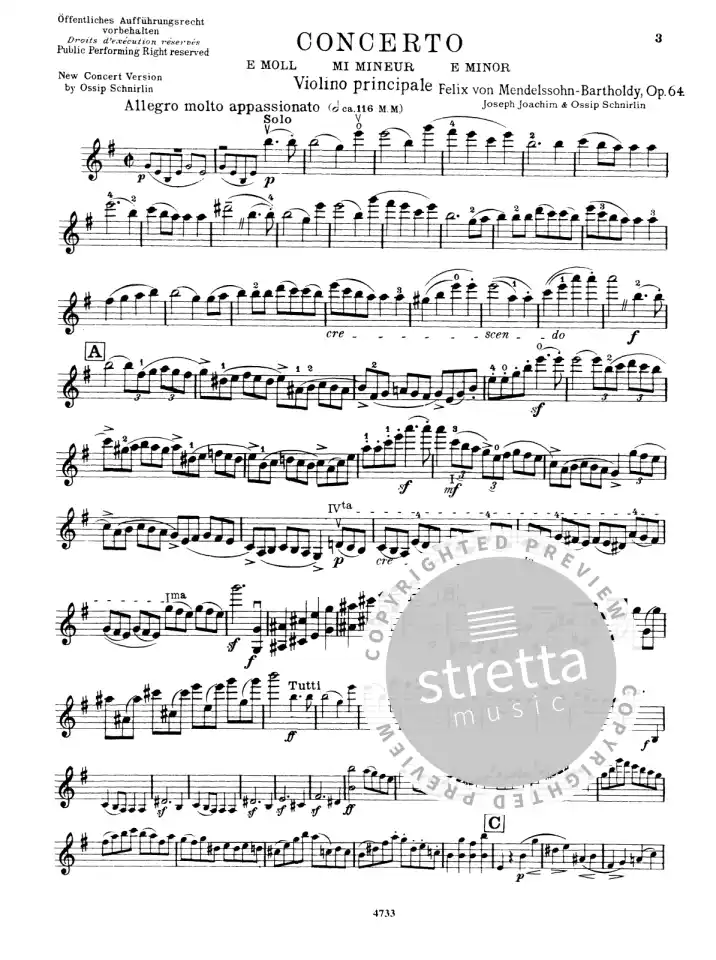

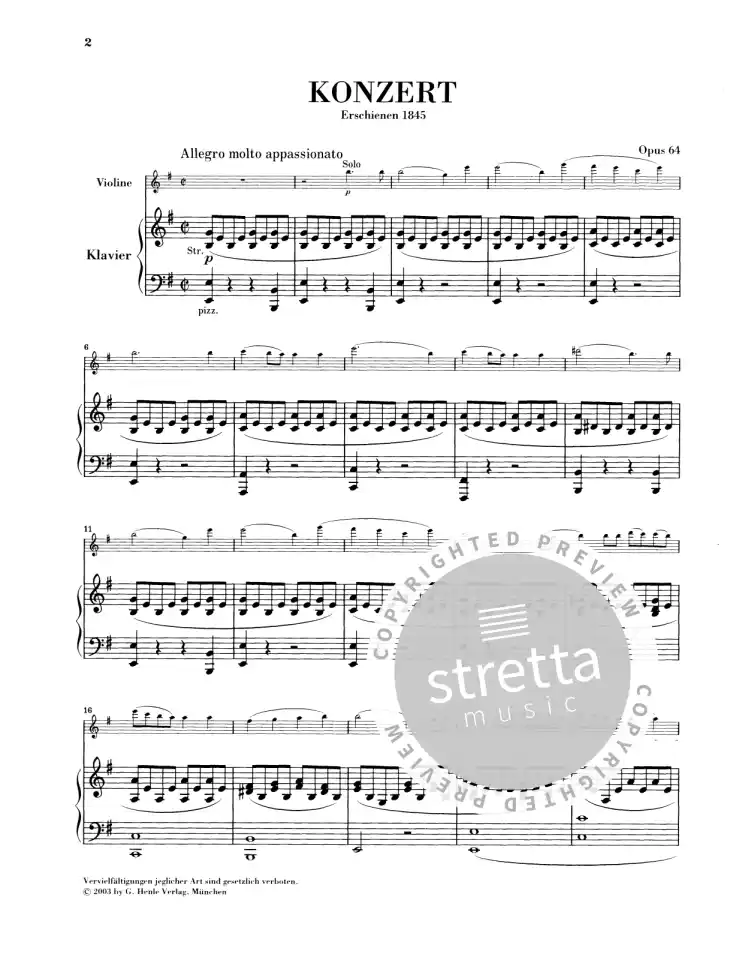

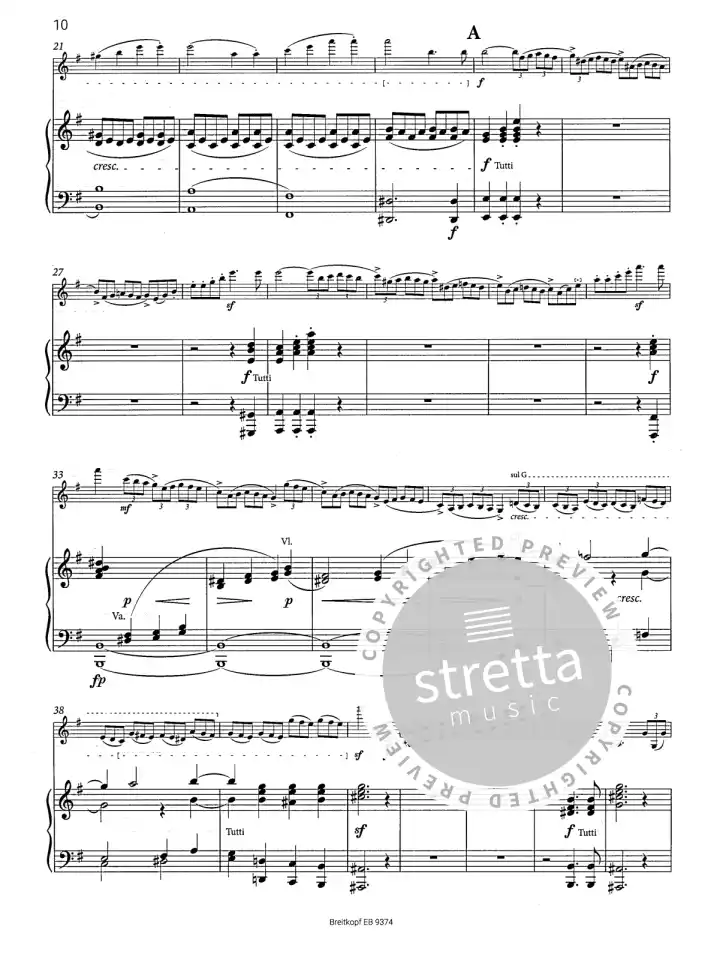

Movement I: Allegro molto appassionato

The first movement, marked Allegro molto appassionato, is in E minor and follows a modified sonata form. It opens with a lyrical and expressive melody played by the solo violin, immediately establishing the concerto's emotional intensity. This melody is unusually presented before the orchestral exposition, a stark departure from traditional concerto form and a characteristic element of Mendelssohn's innovative approach. The orchestra then enters with a more dramatic and forceful statement of the theme. The second theme, in G major, offers a contrasting moment of serenity and beauty. The development section is characterized by a passionate dialogue between the soloist and the orchestra, exploring the thematic material in a variety of keys and textures. A prominent feature is the cadenza, which is integrated into the structure of the movement, emerging organically from the development section rather than being a separate, improvised display of virtuosity. The recapitulation brings back the themes in their original form, with the soloist playing a prominent role. The movement concludes with a brilliant and energetic coda.

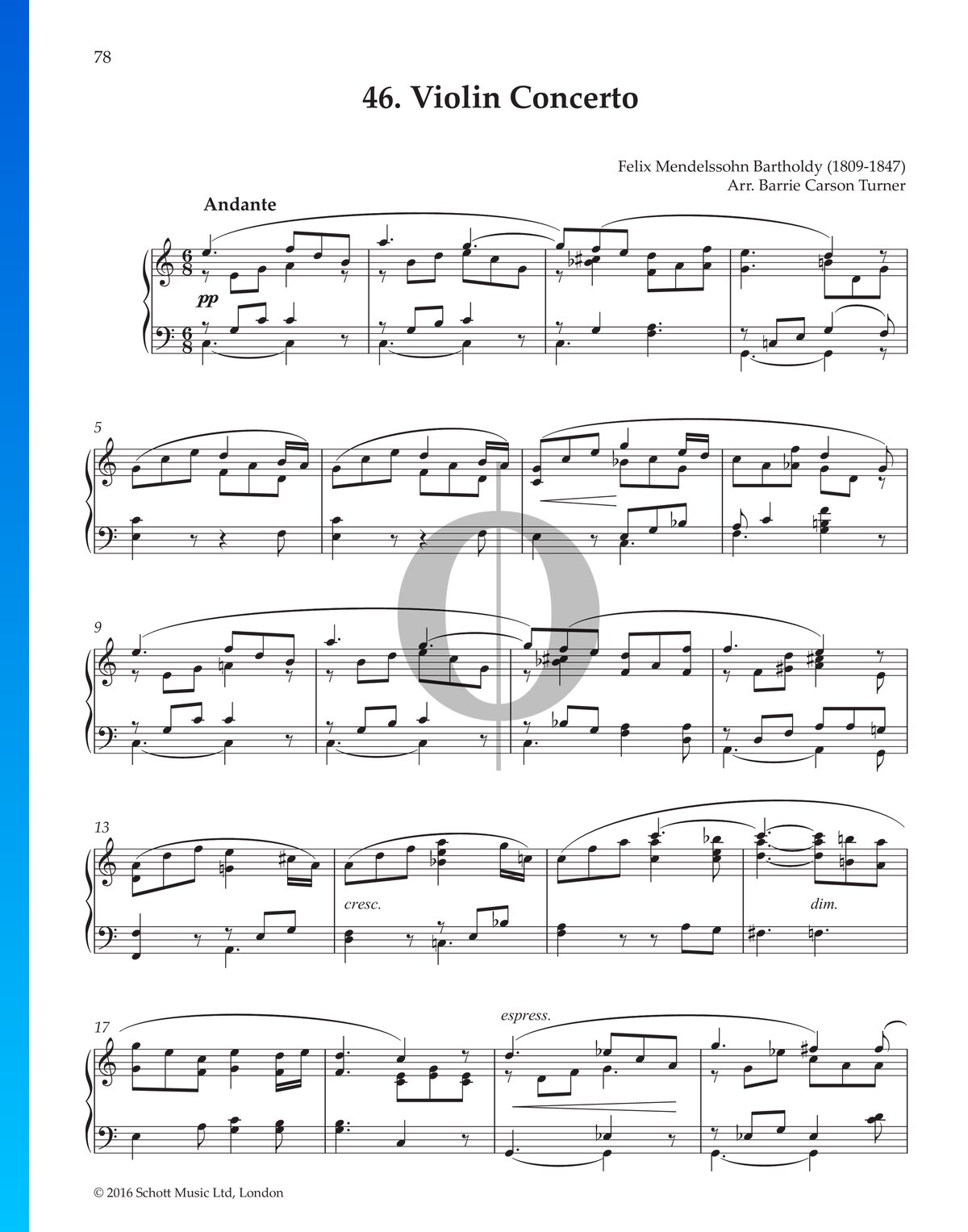

Movement II: Andante

The second movement, marked Andante, is in C major and provides a lyrical and contemplative contrast to the intensity of the first movement. It is cast in a simple ternary form (ABA). The main theme is a beautiful and song-like melody played by the solo violin, accompanied by a delicate and transparent orchestration. The middle section offers a slightly more agitated and expressive character, but the overall mood remains one of tranquility and serenity. The movement concludes with a return to the main theme, providing a sense of closure and resolution. The transition from the first movement to the second is particularly notable; a single sustained note in the bassoon gently leads the listener into the peaceful atmosphere of the Andante, illustrating Mendelssohn's mastery of orchestration and seamless transitions.

Movement III: Allegretto non troppo – Allegro molto vivace

The third movement, marked Allegretto non troppo – Allegro molto vivace, is in E major and provides a brilliant and joyous conclusion to the concerto. It is in sonata-rondo form, combining elements of both sonata and rondo structures. The movement opens with a brief introduction by the orchestra, leading into the main theme, which is a lively and spirited melody played by the solo violin. The movement is characterized by its energetic rhythm, dazzling virtuosity, and playful interplay between the soloist and the orchestra. There are several contrasting episodes, each offering its own distinct character and mood. The movement builds to a thrilling climax, culminating in a triumphant coda that brings the concerto to a satisfying conclusion. The Allegro molto vivace section showcases the violinist's technical capabilities with rapid scales, arpeggios, and double stops, but always in a musically engaging way.

Significance and Legacy

Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E minor is widely considered one of the greatest violin concertos ever written. It has been praised for its melodic beauty, technical brilliance, structural innovation, and emotional depth. The concerto has had a profound influence on subsequent generations of composers and violinists, and it remains a staple of the concert repertoire. It is particularly valued for its balance between virtuosity and musical substance, avoiding empty displays of technical prowess. It is also notable for its intimate and expressive character, conveying a range of emotions from joy and exuberance to sadness and introspection. Its impact on later Romantic concertos is undeniable, setting a new standard for the genre. The concerto helped cement Mendelssohn's reputation as a leading composer of the Romantic era.

The concerto's enduring popularity is due to its accessibility and universal appeal. Its melodies are memorable and immediately engaging, and its emotional content is readily relatable. Moreover, the concerto offers a satisfying balance between challenge and reward for both performers and listeners. It requires a high level of technical skill and musical artistry to perform effectively, but it also offers a rewarding and enriching musical experience. The concerto continues to inspire and delight audiences around the world, solidifying its place as a true masterpiece of Western classical music.

Performing the Concerto

For violinists, Mendelssohn's concerto presents a significant technical and musical challenge. The solo part demands exceptional agility, intonation, and expressiveness. Mastering the rapid passages, lyrical melodies, and intricate double stops requires years of dedicated practice and study. It's not just about technical proficiency; a deep understanding of the concerto's emotional content and structural nuances is essential for a compelling performance. Many renowned violinists, including Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, and Anne-Sophie Mutter, have recorded and performed the concerto, each bringing their own unique interpretation to the work. Listening to these different interpretations can provide valuable insights into the concerto's multifaceted character.

The orchestral part is equally important in creating a successful performance. The orchestra must provide a supportive and nuanced accompaniment to the soloist, carefully balancing its sound to allow the violin to shine. The interplay between the soloist and the orchestra is a crucial element of the concerto's overall effect. A good conductor will ensure that the orchestra and soloist are working together in harmony, creating a seamless and unified musical experience.

Listening Recommendations

There are countless recordings of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto available, offering a wide range of interpretations. Some highly regarded recordings include:

- Jascha Heifetz with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Charles Munch

- David Oistrakh with the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Eugene Ormandy

- Anne-Sophie Mutter with the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Herbert von Karajan

- Hilary Hahn with the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Hugh Wolff

These recordings offer a diverse range of approaches to the concerto, showcasing the different facets of its musical character. Listening to these recordings can provide a valuable and enriching experience for anyone seeking to deepen their understanding and appreciation of this timeless masterpiece. Beyond these, explore recordings by historical figures like Joseph Joachim and Fritz Kreisler to gain insight into performance practices closer to Mendelssohn's time. Remember to consider the recording quality and the orchestra's performance alongside the soloist's interpretation.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4632845-1370603827-9112.jpeg.jpg)